RePost (Regarding Exhibition Publication Opportunities) features ongoing work by Waterloo Architecture students, faculty, and alumni that has been exhibited, published, or presented in other venues. We welcome submissions at submit@waterlooarchitecture.com

This article was written during some of my travels between undergrad and masters, and was published in On Site 25: Identity.

Nine halmoni (the polite form of address for elderly women in Korean) sit cross-legged on the linoleum, a shallow dish of kimchi and some rice between them. As the food dwindles, their chatter undying, one rises, slides open the screen door, and unhooks her barbers’ shears from a peg on the courtyard wall. Amid eager gestures from the other women, a second halmoni seats herself before the mirror and lets the hairdresser pin a robe under her chin.

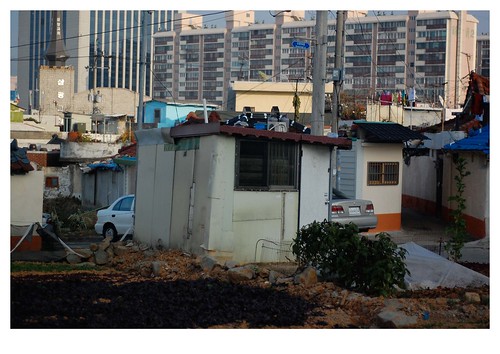

Geum-soon has lived and worked in the neighbourhood behind Yangdong Market in Gwangju, South Korea for thirty years, running an unlicensed hair salon out of her home. Her customers are her long-time neighbours. In these colonies of low-rise houses dating from the 1960s, an aging population supports itself on simple skills. Fortune tellers’ poles pierce the air, flapping canvasses delineate makeshift restaurants, and parked outside a few gates are metal wheelbarrows, used to collect scrap materials and garbage from around the city.

These neighbourhoods are a vestige of industrializing Korea. During president Park Chung-hee’s 1961-1979 dictatorial rule, rapid economic expansion brought an influx of rural workers into cities like Gwangju. At the same time, traditional chogajibs (thatched-roof homes) were ubiquitously standardized with widely available industrial materials under a political initiative for social development, the Saemaul (New Community) Movement. Using the new slabijib (slab-roof home) prototype, housing for migrant workers could be built quickly, economically and en masse. Concrete block replaced vernacular wall assemblies of straw-bale and rice paper, and concrete or corrugated metal also replaced the thatched roofs that had to be rebuilt every summer in a chogajib. The efficiency of slab construction superceded classical building methods.

In these settlements, where the urban lower and middle class live today, Saemaul’s motto “Diligence, Self-Reliance, and Cooperation” is still evident. Tenants grow enough food for their own use on rooftop gardens and in communal vegetable plots, sharing their harvests. Geum-soon, who serves a complimentary meal with her 8,000-won haircuts, has minimal expenses: “I don’t have to pay [a separate] rent for the shop, or taxes. The food I grow outside, some my neighbours give me.”

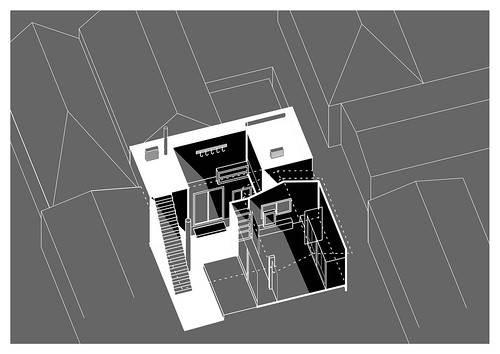

Several halmoni sit out on the courtyard porch, laughing and passing snacks back and forth while Geum-soon perms her friend’s hair. A slabijib follows certain essential principles of Korean house design: the main house and several outbuildings are positioned around a central courtyard, which is an open-air living room. In the city, this is often a narrow, unbuilt gap. Geum-soon’s neighbours socialize in her covered courtyard, but it also doubles as a utilitarian space, crowded by wash basins, cookie tins and soda bottles, extra furniture and old appliances. A modern washroom, a charcoal briquette furnace, and two storerooms open off of it.

Geum-soon’s small home is modernized and well-maintained. She has lacquered furniture, a TV, and her 29-year-old daughter, who lives with her, has a desktop computer with internet. The interiors are dim, with only small windows facing the courtyard, to keep cool in the summer and to minimize heat loss in the winter. Geum-soon has upgraded her windows to durable double-glazed units. In a vast contrast, less prosperous homes in the same neighbourhood rely on styrofoam, plastic bags, and other found materials to seal cracks against wind and rain. Some staple green garden netting over the translucent rice paper window screens, traditionally designed to mediate light and humidity, for reinforcement.

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) estimates that almost one in every two elderly households in South Korea live in poverty, making South Korea’s elderly poverty rate the highest amongst OECD nations.[1] This is largely attributed to a paradigm shift from traditional family structures. Where aging parents once depended upon their grown children to support them, this is less common today. National pension, instigated in the mid-1990s, does not service a previously retired or self-employed population.

Slabijibs are a low-rent accommodation choice in the city centre, in the vicinity of transportation networks and employment opportunities. Occasionally, a young family moves in to save money, but the predominantly elderly population has lived here for decades. Despite a prevailing cultural desire for the old to live with their sons, some choose to remain in these communities where they are independent, self-sustainable, and have familiar old friends.

Generally viewed as bland, outdated structures, as well as a painful reminder of a period of political oppression, these tenements have nevertheless acquired their own character through decades of inhabitation. Renewals and repairs have transformed the standard building envelope, and even as they are abandoned, the structures take on the beautiful texture of decay. Without maintenance, they deteriorate rapidly: built to embrace the environment, wild grasses and vines easily take root in cement crevices, rapidly turning a house into a site of ecological succession.

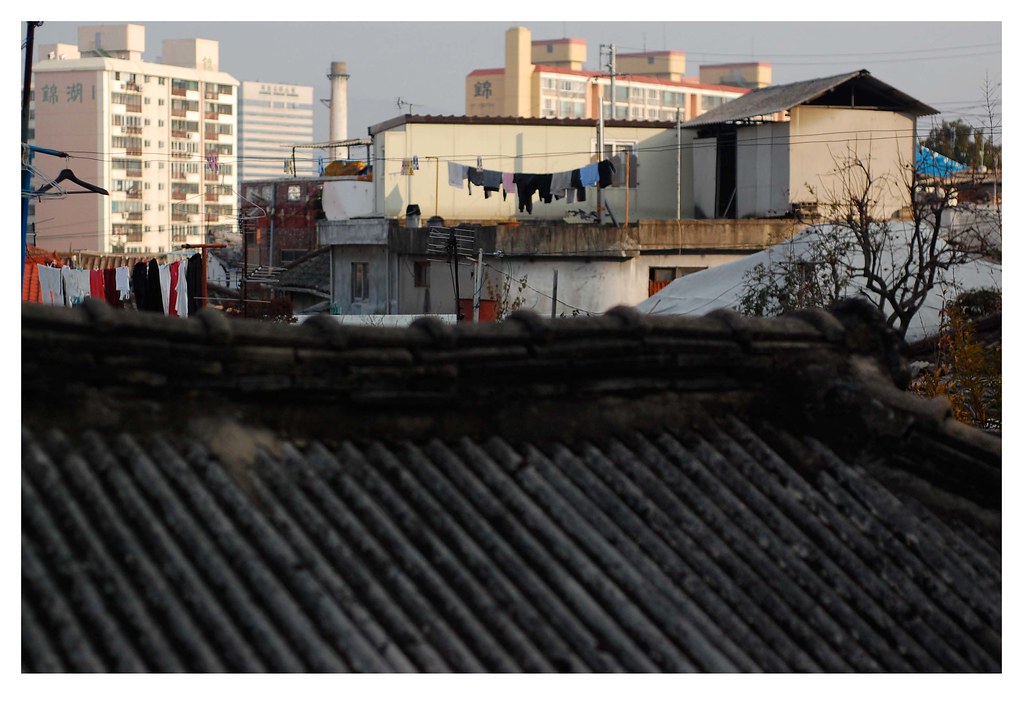

From the courtyard, a concrete staircase reaches the roof. The slab roof gives each tenant access to his or her own roof terrace, useful for household chores. On Geum-soon’s terrace, hot peppers are spread out on a mat between utility pipes, and laundry and fish dry on the same line. Moreover, neighbours can see one another as they go about their daily chores on the roof, holding conversations over the barriers of their cement walls. The roof makes a lively second tier of community space.

The view of the Saemaul colony – bright painted walls, crowded terraces, all the texture of life and decay sparkled in the afternoon light. Between the houses, there are maze-like corridors that switch back and forth, informally reinforcing the mountainous Korean landscape. Though a product of industrialization, in their use, disuse, and gradual disintegration, these settlements have a strange kinship with nature.